.jpg) |

| Alley in Amsterdam |

Can any art purport to be pure? Can any artist claim no

concern for his audience? Can ‘art’ be deigned ‘art’ without a viewer?

Some might judge artwork on its technical merits or daring,

others might judge it on its ability to engage and hold the viewer’s attention,

still others on its ability to express something profound or deeply personal, or

simply to dazzle with sheer beauty.

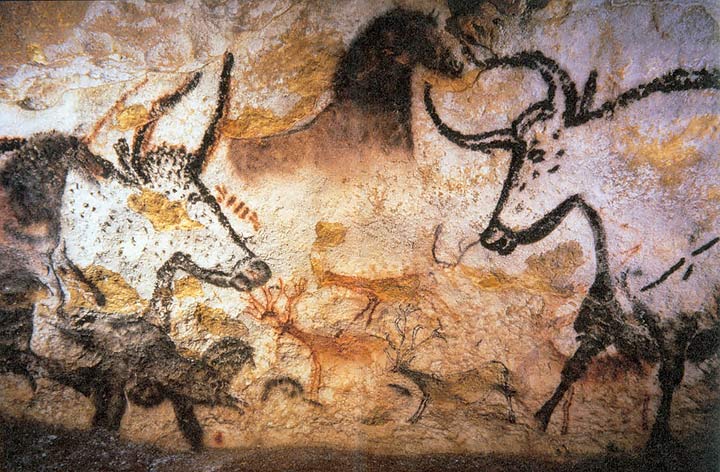

Historically, artwork was most likely produced as a record

of events, to tell a story, or provide guidance to others—as in

Lascaux. The earliest

‘histories’ are likely in the oral tradition, rather than written or rendered in

any visual form.

And for all we know man

may have been scraping pictures into the soil or rocks long before he invented

the means to paint them on the walls of caves.

But cave drawings predate other forms of proto-writing, hieroglyphs or

runes as a human record of concepts or ideas.

Interestingly, even among the earliest

drawings thus far discovered, there is a hierarchy of style and beauty—perhaps

by the standards of our modern perspective, but perhaps not.

The most extensive and elaborate cave

paintings also tend to be the most stylistically and technically impressive

renderings—this would support the notion of a more talented, practiced or

inspired painter.

While there are many theories about the purpose of the

images most can agree that this was the beginning of visual ‘art’ as

a medium of expression for mental imagery. Whether the images were made

as histories of events, teaching tools for hunting techniques, a record of

sacred animals or ceremonies, it will be hard to ever know for certain, but the

images convey stories, even if we are not certain what those stories are.

Some clue to the historic use of cave drawings might be found

in contemporary times. The aboriginal culture of Australia may be one of the longest

isolated and most enduring cultures that have continually produced paintings similar to those in

Lascaux. The aboriginal culture could in some senses be seen as a sort of time

capsule of the past, that because isolated, retained and passed down many

features of the prehistoric painting practices. These practices have, of

course, evolved, but in more isolation that in most other parts of the world.

Certain features of the practices and uses of ‘cave painting’ among the

Australian aborigines, could give us some insights into the prehistoric uses of

visual representation; these appear to include the use of imagery as teaching or

mapping tools, and the development of these tools into powerful visual symbols

recognizable to the entire culture—as exampled by the circular 'water hole' symbol in rock paintings at Uluru or images carved into trees in the Blue Mountains.

.jpg)

During the period of exposure to the wider cultural representational practices of the world over the last 300 years,

aboriginal painting has branched into non-traditional modes of expression; paintings using paints from natural pigments on tree bark, and more currently the use of acrylic paints on canvas.

.jpg) |

| Aboriginal paintings on bark in natural paints |

.jpg) |

| Large contemporary aboriginal painting in acrylics |

This transition may be a sort of fast forward for what happened over more than 40,000 years of cultural change in the wider world.

In classical antiquity—in the fertile crescent—painting developed from its 'cave art' roots into more elaborate forms of relief sculpture, murals and mosaics, both as a

records of events and as ceremonial tributes to the ideological ‘gods.’

|

| Assyrian relief in the British Museum |

Stylistic

patterns evolved and cycled as techniques and mediums changed.

.JPG) |

| Painting on wall in Knossos - Crete, Greece |

.JPG) |

| Fresco on walls and mosaic floor in Pompeii, Italy |

Over time

imagery also took on a decorative function and man developed an ‘aesthetic’ for

judging beauty by comparing works of art.

But the art of comparison

itself is a hard-wired instinct that has evolved in almost all forms of life,

probably for the purposes of finding the ideal mate. Our

surroundings are scanned through our senses and sorted by importance or value. Eyesight is perhaps man’s most highly utilized

sense, and through it the art of judging beauty or perfection begins. Drawn imagery could

also be said to have provided the basis of early forms of writing—as in the

Egyptian hieroglyphs or

Chinese calligraphy. Pictures became symbols, and these

symbols as a visual language, likely predate spoken language.

Characters in most Asian languages

still draw on imagery as symbolic ideas, rather than on the western use of sound sequence.

Throughout historic time visual representations through a variety of mediums have

flourished and grown in complexity. Uses of art and the means to produce art have expanded.

Art has always depicted elements of reality and imagination, and as a narrative, may contain calculated degrees of truth. So inevitably it became increasingly useful for consolidation of

power—for propaganda—its purpose going well beyond simply capturing likenesses or recording events. Caesars glorified

their triumphs, churches illustrated the loving deeds of their saints

and advertised the rewards of prayer and sin, monarchs surrounded themselves with images of pastoral beauty and Bacchanal revelry, the rich

commissioned portraits of themselves or their loved ones and murals to decorate the walls of their palaces.

|

| Church in Füssen, Germany |

Decoratively,

art began to orchestrate beauty, rather than mimicking ‘found’ beauty, and came to exemplify elite status. Symbolically, art developed its own language of tropes and references. Works of art were in conversation with each other, through the viewer. And as art

became a marketable commodity it also became more valuable.

The art market in contemporary times has become a cutthroat business.

Artists produce work, which they try to market in exchange for fame, money, goods or

services—think Andy Worhol as a prime example. Graphic art has evolved into a

powerful tool of commercial persuasion and influence. But the confounder of the commercial art market was the advent of photography. Suddenly, the camera could instantly capture a likeness or scene and photography competed with fine art as 'documentation.' It soon also developed its own mode of expression—throwing into crisis the use of an artist toiling away on a painting or sculpture unless his artwork expressed something photography could not. Fine art found its niche by celebrating the artist's perspective—the differences between what can be captured by a camera lens and what man perceives from his surroundings, or what his imagination invents. Fine art began to challenge all historic boundaries, and the conversation of art became more radical, because only in being new and unique, could it justify its commercial or artistic value.

Fine art in many forms is both craft

and income for the artist—whether or not it contributes commentary to art’s fundamental philosophical purpose. But as a marketable commodity, it can hardly escape its need for a purpose.

Fine art can be safe and traditional, selling itself on its elegance and handcrafted singularity, or it can sell itself through daring, by challenging contemporary concepts of taste or acceptability—regardless of its appeal to a prospective buyer.

Since the dawn of painting, among other motivations, art has surely been produced, at times, purely

for the sake of expression—in order to speak directly to an audience who may or may not

wish to acknowledge or support it. Art has always been ungovernable when produced

without patronage.

And as it is created by

the hand of man, it may be used as a means of defiance against the very

power structures that would like to control it—as a weapon against the artist’s

'enemy'—whomever or whatever that may be.

.jpg) |

| Graffiti on mailbox in Wellington, New Zealand |

One must really go back to the term ‘art’ to define what it

is. ‘Art’ would seem to be a collectively agreed upon skill—the ‘art’ of…metal

working, basket-weaving, or in this case, rendering through paint or 3-dimentional mediums. Regardless of the form—a collectively

determined skill—in order to be an ‘art’, must be compared and judged. Someone, if only the artist himself, must deem

the work to be of higher value than that of a more mundane and rudimentary

counterpart. The status of ‘art’ must be earned socially and collectively. Consequently, at the root of

all art there is comparison and judgment. The artist must always dance with his audience—whether that audience is only the viewer himself, or includes a friend or relative, an agent, a gallery owner, another artist, a patron, or an

indifferent passerby.

|

| Painted wall in Athens, Greece |

And whether we like it or not, art must sell

itself—in both senses of the word—as a commodity, as propaganda, as an

investment, as a historic record, as commentary, as self expression, or as

defiance or rebellion.

|

| Graffiti on wall in Genoa, Italy |

|

| Naples, Italy |

If we follow the evolution of art to its current spectrum of forms,

we might find calculated refinement at one end and pure spontaneity at the other.

.JPG) |

| One of a number of pieces painted on columns under a freeway in Warsaw. |

So we are compelled to ask whether one mode expresses the heart of man more fully than the other.

.jpg) |

| Graffiti on wall in Amsterdam |

All art incorporates man’s internal vision and is produced

for man’s consumption. But some art—like some ideas—seems to prostitute itself

to a lesser degree. Graffiti—‘street art’—seems to ask for nothing but the

viewer’s attention and takes art almost full circle to its ‘cave art’ roots as a visual

cultural expression in public view.

|

| A bit of whimsy in Palermo, Sicily |

.JPG) |

Whimsical graffiti on a wall in Krackow, in the old Jewish ghetto.

|

|

| Palermo, Sicily |

Graffiti records the artist’s perspective

and yet asks for no compensation.

.jpg) |

| Graffiti on wall in Lisbon, Portugal |

Certainly graffiti can also be vandalism. As expressions of

defiance, or ‘peeing on the fire hydrant’, ‘tags’ are territorial symbols. They

attempt to usurp things owned by others, in defiance of the boundaries of the

established rights of ownership.

.JPG) |

| Graffiti in Budapest, Hungary |

I don’t condone ‘tagging’—I actually detest

it, but I do admire graffiti as ‘public’ visual expression when it makes a point, or enriches

the cityscape, rather than defaces or defiles it.

|

| Section of the Berlin Wall |

.jpg) |

| Alley in Melbourne, Australia |

|

| Alley in Palermo, Sicily |

Public commentary in the form of graffiti was apparently already around in ancient times.

|

| Interior wall in Herculaneum, Italy |

What defiles or enhances, however, is always a subjective

determination, for what offends one person is never the same as what might

offend the next.

.JPG) |

| In Kazimierz, a suburb of Krackow. |

|

| Wall in Palermo, Sicily |

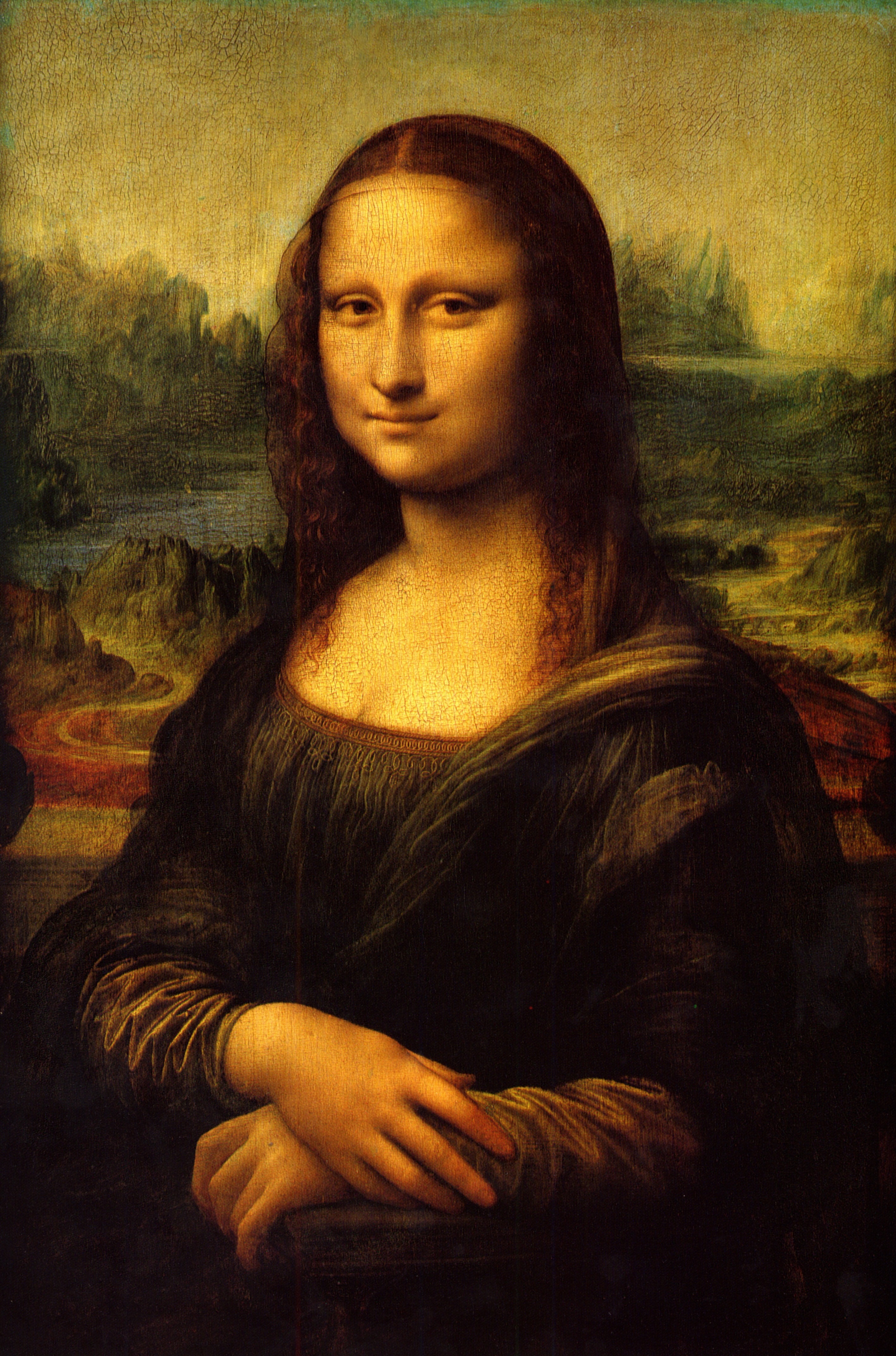

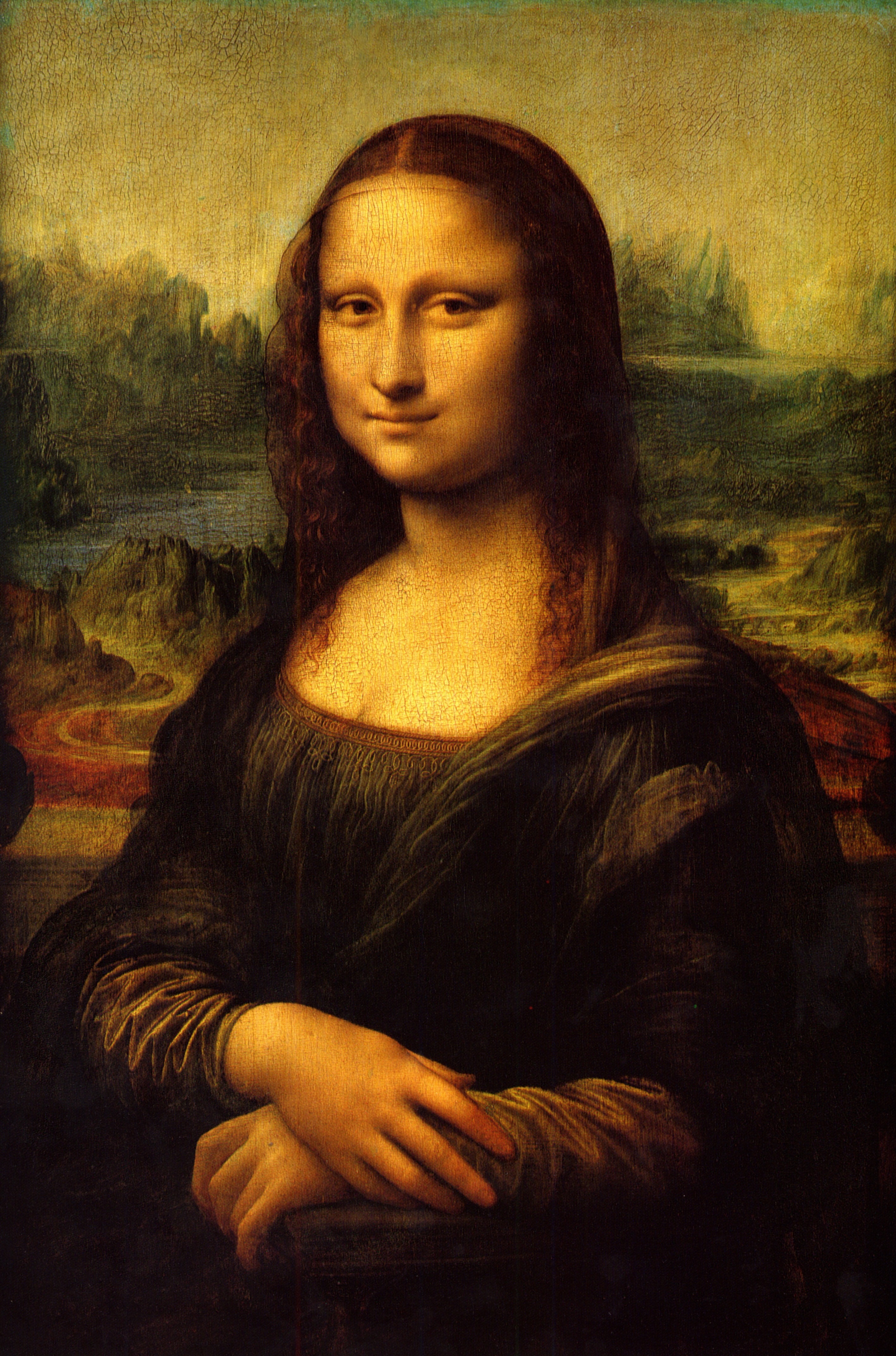

There are Mona Lisa’s even in the world of graffiti.

.jpg) |

| Graffiti on door in Barcelona, Spain |

.jpg) |

| Alley in Melbourne, Australia |

|

| Alley in Palermo, Sicily |

Graffiti asks for nothing but a moment or two of one's time and attention.

.jpg) |

| Carving on rock ledge in an abandoned quarry on Portland Bill, England |

.jpg) |

| Carving on rock face in an abandoned quarry on Portland Bill, England |

.JPG) |

| Ode to Chopin, Warsaw. |

.jpg) |

| Sidewalk art in Fremantle, Australia |

|

| Michael, on wall in Melbourne, Australia |

Graffiti invites contemplation and challenges the boundaries of what 'art' has become in our contemporary landscape, spoken directly from artist to audience. It is one of the most visceral and spontaneous forms of direct expression in our modern world.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)